Austro-Daimler ADS R ‘Sascha’ celebrates centenary of its class victory at the Targa Florio

At Porsche, there has always been a tradition of building small, lightweight sports cars with innovative technology. Another common thread that weaves through the company’s history is the sports car manufacturer’s custom of proving its innovations in motor racing before they go into series production. It was exactly one hundred years ago that Ferdinand Porsche, then Head of Development and Production at Austro-Daimler, used the extreme demands of motorsport to demonstrate his ideas. And with success: the Austro-Daimler ADS R won the Targa Florio on 2 April 1922 against strong competition in the smallest displacement class, taking class victory in the mountains of Sicily.

With the Austro-Daimler ADS R, the then 46-year-old Ferdinand Porsche placed his faith in the principle of the power-to-weight ratio, to this day a defining feature of all sports cars from Zuffenhausen. A century later, a team from the Porsche Heritage and Museum department undertook the restoration of this historic car.

History of the Austro-Daimler ADS R

Ferdinand Porsche first met Count Alexander Joseph von Kolowrat-Krakowsky in 1921. The keen motorsport fan was a partner in Austro-Daimler, the company where Porsche worked at the time. His nickname was Sascha. Porsche and Kolowrat talked about bringing a shared vision to fruition: a small car built in large quantities at a low price. Porsche needed the approval of the executive board at Austro-Daimler for the car but the board was sceptical. However, Porsche was convinced that positive publicity after a successful race would win over his critics. In addition to the production version of his small car with its engine of only 1100 cc, he also built a racing version: the ADS R. As it was financed by industrial tycoon and film producer Kolowrat, the car was named after him: Sascha. The result was a lightweight, two-seat, racing version of the planned series four-seater weighing just 598 kg.

Count Alexander Kolowrat (l.), Austro-Daimler, car race Riesrennen, Graz, Austria, 1922, Porsche AG

Its water-cooled, 1.1-litre, in-line, four-cylinder engine had two overhead camshafts and was set well back in the chassis. This helped to give a weight distribution of 53 per cent front and 47 per cent rear, and with two full petrol tanks and two seats occupied, the load was perfectly distributed. The second bucket seat was reserved for the mechanic, which was not unusual at the time. The mechanic stowed spare parts and tools in a wooden crate behind the seats, and spare wheels were secured at the sides.

Longstanding tradition: Porsche tests developments in motorsport

Although he left Austro-Daimler over disagreements, Ferdinand Porsche’s 17 successful years there proved to be a springboard and he joined Daimler in Stuttgart at the end of April 1923. While working on the small car project he’d met the men who would later be his first employees: Otto Zadnik and Karl Rabe. The latter would be his successor at Austro-Daimler.

A few years later in 1931, together with his son-in-law Anton Piëch and the former racing driver and businessman Adolf Rosenberger, Porsche founded the engineering office ’Dr. Ing. h.c. F. Porsche GmbH, Konstruktionen und Beratung für Motoren und Fahrzeuge’. Porsche would go on to maintain the custom of testing developments in motorsport before they went into series production. And the company would continue to attach special importance to the Targa Florio.

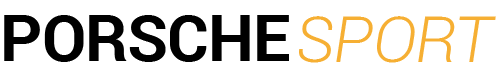

The 13th Targa Florio race, 2 April 1922, Porsche AG

“Strange race over hair-raising routes”

The four ADS R prototypes were only finished shortly before the race in 1922. It was only on the train that they painted the aluminium bodies of the Sascha cars red so they wouldn’t stand out so much and be stolen in Italy. To help tell them apart from a distance, Kolowrat had them adorned with symbols from playing cards.

His model was bedecked in hearts, while Alfred Neubauer – the most successful driver and later the racing director of Mercedes – got diamonds, Fritz Kuhn drove with spades and Lambert Pöcher with clubs. Count Kolowrat not only financed and directed the operation, but also drove too, entering the small sports cars in the 1.1-litre class, which set off first. Later, the four Sascha drivers would call the Targa Florio a “strange race over hair-raising routes”. The cars left at two-minute intervals, which meant that the participants never saw who they were competing against.

The 13th Targa Florio race on 2 April 1922: Report in the Allgemeine Automobil-Zeitung about the success of the Austro-Daimler racing car "Sascha" at the Targa Florio 1922.

The aim was to complete four laps of 108 kilometres each. At the end – after 432 km, 6,000 turns and gradients of up to 12.5 per cent – the leading Austro-Daimler ADS R finished 19th in the overall rankings. “Many strutted their stuff with big engines at the Targa Florio but the 598-kg Sascha was a nimble fellow with its 50 PS at 4500 rpm,” says Achim Stejskal, Director of Heritage and Porsche Museum. “At the end of the race, its average speed was just 8 km/h less than that of the fastest cars with engines four or five times more powerful.”

21 May 1922, Spain, Armangué Trophy Tarragona. At the wheel of the Austro-Daimler "Sascha" with the starting number 19 Alfred Neubauer.

The Italian press hailed the fast and resilient “mini car” with a potential top speed of 144 km/h as “the revelation of the Targa Florio”. To spread the news beyond Italy’s borders, Ferdinand Porsche placed large adverts in newspapers: “Austro-Daimler is the moral victor of the 1922 Targa Florio!” It was a claim challenged just days later by Daimler, which placed large ads of its own; Daimler had, after all, taken overall victory. The members of the executive board of Austro-Daimler AG – headed by Camillo Castiglioni – had indeed taken note as Porsche had hoped but were still not prepared to approve series production of the ADS.

Further successes did not change their view. The agile and efficient Sascha followed up its class win in the Targa Florio with another 42 victories in 52 races – often with the young Ferry Porsche watching on. The board ultimately rejected the proposal once and for all, citing financial reasons, inflation and the fact that Austria was too small to offer a suitable market. They believed their focus should be on big, six-cylinder models instead. The board’s decision and a conflict with Castiglioni led Porsche to leave Austro-Daimler and move to the parent company in Stuttgart. In 1924, Ferdinand Porsche took part in the Targa Florio with Daimler and received, among other things, the honorary doctorate title – the title that still features in the company name today.

Porsche: the most successful entrant in the Targa Florio

What his father Ferdinand Porsche started a century ago as an employee of Austro-Daimler, Ferry Porsche continued with cars under the family’s own name, the Stuttgart sports car manufacturer becoming a regular competitor in Sicily. And with 11 overall victories, Porsche was the most successful participant in the Targa Florio of all time. In 1956, Umberto Maglioli scored Porsche’s first outright win in the 550 A Spyder. Maglioli’s victory evoked what the team led by Ferdinand Porsche and Count Kolowrat achieved a hundred years ago with the Austro-Daimler ADS R: besting a field of competitors with bigger engines.

Restoration of the Austro-Daimler ADS R

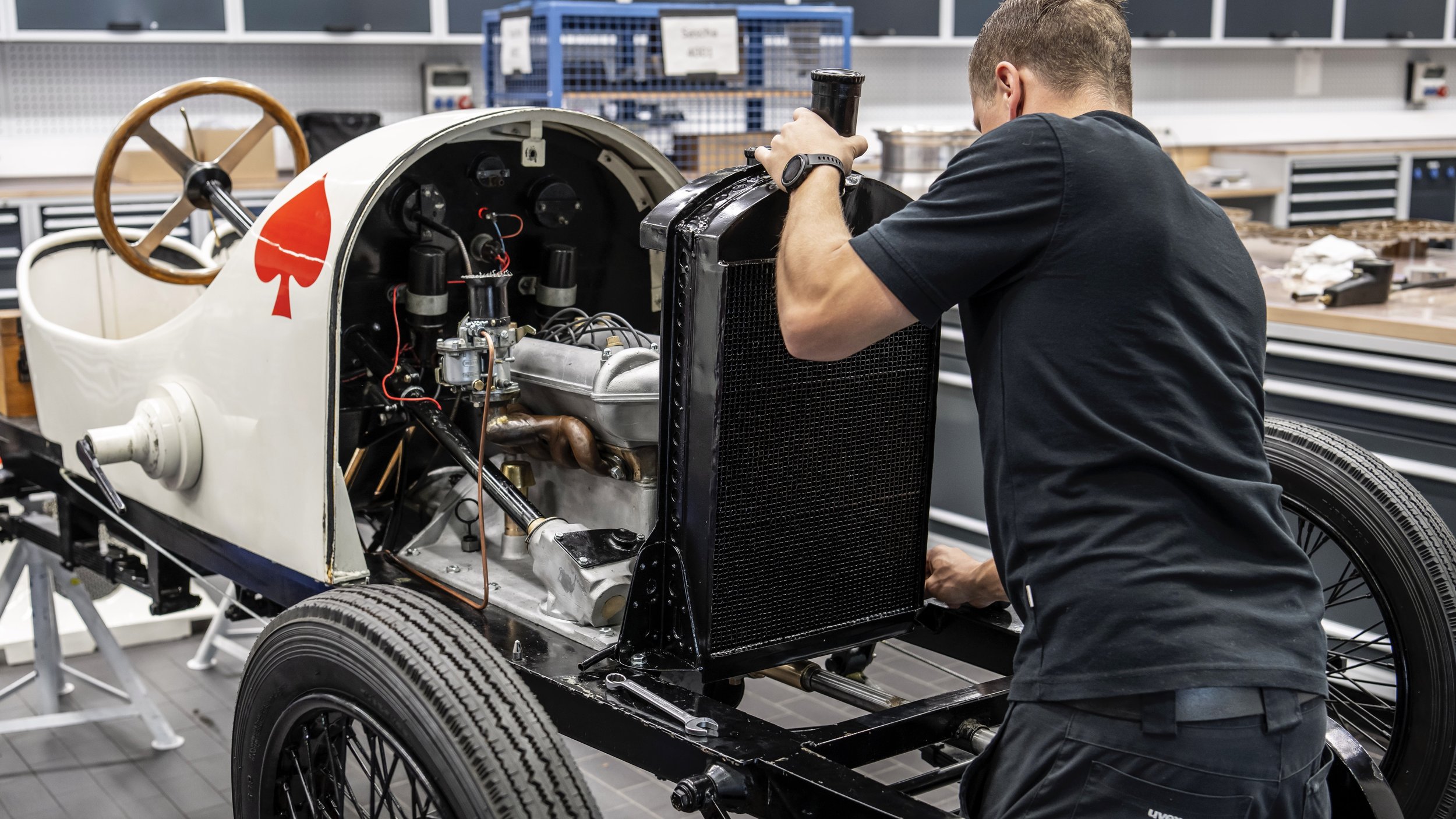

The vehicle had been part of the exhibition at the Porsche Museum for many years before restoration work began. A small brass plate on the dashboard indicates that the racing car was last restored in Porsche’s training workshop in June 1975.

“We did some research and found out that the car came into the shop at the end of the 1950s and was repaired there in a contemporary way,” says Kuno Werner, supervisor at the Porsche Museum, who is in charge of the project. Back in 2021, he and his team set themselves the goal of restoring the Sascha in time for the 100th anniversary of its very first class win. “Our aspiration was to reconstruct the star of the Targa Florio in a way that is worthy of historic preservation and make it road worthy,” says Werner. “To rebuild the Sascha from scratch was out of the question since so much of it was no longer original.”

Before the start of the restoration, Werner was given the opportunity to pay a visit to Sascha’s sister car in Hamburg, which is in almost original condition and painted red. The Sascha from the exhibition was also red until 1975, at which point the workshop staff painted it white. Back at the Porsche Museum, Werner pored over old notes in the company archive. There, in the memory bank of Porsche, the sports car manufacturer keeps important documents that are helpful as historical evidence when working on old vehicles. For example, Werner learned that the vehicle stood on a farm for years after all the racing and was, to a degree, scavenged for parts.

After an initial test run of a few metres, it turned out that the engine was leaking. “The more parts we dismantled, the clearer it became that we needed a proper foundation. After all, you don’t build a house on sand,” says Werner, explaining the decision to have the engine overhauled by an expert in pre-war engine construction. The key here was to understand what modifications had been made in past decades. “Overhauling the cylinders and fitting them into the original housing was a particularly exciting phase for everyone,” says Werner.

Restoration of the oldest vehicle at the Porsche Museum

At that point, Werner handed over the restoration of the oldest vehicle at the Porsche Museum to his youngest employee for the next six months. Jan Heidak, a technician at the museum, got right down to work with the engine builder. “I like preserving technical, cultural heritage,” says the 28-year-old. He sought out former technicians, now pensioners, who were familiar with the engineering practices of yesteryear and were happy to share their insights.

In its quest to keep historical technology alive, the Porsche Museum sees it as its special duty to ensure the transfer of knowledge to the next generation. For half a year, the team dedicated its attention to the rigid axle suspension, the brakes and the engine. The character of the four-cylinder engine with its 68.3 mm bore and 75.0 mm stroke was soon defined: it had to be responsive and sporty. The Austro-Daimler ADS R, after all, contained many of the genes that would later become the foundation of Porsche. First and foremost, lightweight construction.

Technology of the Austro-Daimler ADS R

Sascha was ahead of its time when it was developed more than a hundred years ago. For example, the driver actuated the four drum brakes mechanically by means of cable pulls, which, of course, were replaced with new cables during the restoration. Central nuts kept the wheels on, and the gearshift for the four-speed gearbox was inside the vehicle – both innovative for the 1920s. The engine had steel cylinder liners, light-alloy pistons and even a dry-sump lubrication system. It also featured dual ignition – a technical innovation adopted from racing, probably for reasons of safety. There were two spark plugs per cylinder.

If one spark plug failed, the engine could still run on all cylinders. Compared to other racing engines of the time, Porsche’s four-cylinder engine with a larger bore and shorter stroke proved to be the most advanced concept hands down. The exhaust manifold was funnel-shaped and well-thought-out: the exhaust ports of the middle cylinders converged in a shared manifold, as did the two outer ones. Further down, the two merged in a single pipe and accelerated the exit velocity of the exhaust gases.

At the rollout, after more than six months of work, Jan Heidak, who was responsible for the restoration of the oldest vehicle in the Porsche Museum, was finally allowed behind the large wooden steering wheel. “It’s amazingly good for a hundred-year-old car,” he said after his first drive in the pre-war vehicle on the skid pad at the Development Centre in Weissach. However, the arrangement of the pedals, which is not the same as it is nowadays, took some getting used to. The middle pedal is for accelerating rather than braking. Moreover, he said, the steering forces are high and the steering has no self-centering – to his mind the greatest difference to new vehicles today. “The shift is very good; it works without double declutching up and down, although it feels better if you do. It’s like a Porsche 356,” Heidak concludes. He does not recommend driving without goggles, however: “The front wheels kick up a lot of dirt, which flies right up in your face along with little stones.”

Kuno Werner reveals the Porsche Museum’s plans for the Sascha: “Interested parties will find it ready to drive at many events.” There’s certainly no shortage of opportunities in the Porsche Heritage and Museum department calendar.