IROC - Eliminating ‘The Unfair Advantage’

Motorsport fanatics often struggle to construct an argument against the uninformed view of “Well they only win because they have the best car, that isn’t sport.” Of course, the truth of gaining an advantage with superior equipment is hard to ignore. However, only the very best drivers negotiate the pitfalls in and out of the car to reach the very top. To simply write off a racing champion due to an equipment advantage is disrespectful to the work and skill involved.

Single make racing is common in modern motorsport. Even world class series like IndyCar mandate identical chassis from Dallara in an attempt to promote parity. However, the reality is that the largest teams can still deploy their superior resources to find a performance advantage. Furthermore, hiring the best drivers remains a privilege reserved for the lavishly backed organisations.

Nearly fifty years ago, a race team owner renowned for seeking ‘The Unfair Advantage’ conceived a series that aimed to find the ultimate racing champion. Roger Penske’s vision was to gather the best drivers from sports cars, stock cars and open wheel competition and pit them against one another in identical cars. Therefore, creating the elusive even playing field.

For ‘The International Race of Champions’ (IROC), Penske signed up megastars like A.J Foyt, Richard Petty, Emerson Fittipaldi and Mark Donohue. Each identical car would be prepared by Penske’s meticulous mechanics and allocated with barely enough time to apply the driver’s name before the races began. Thus, eliminating any last minute special treatment.

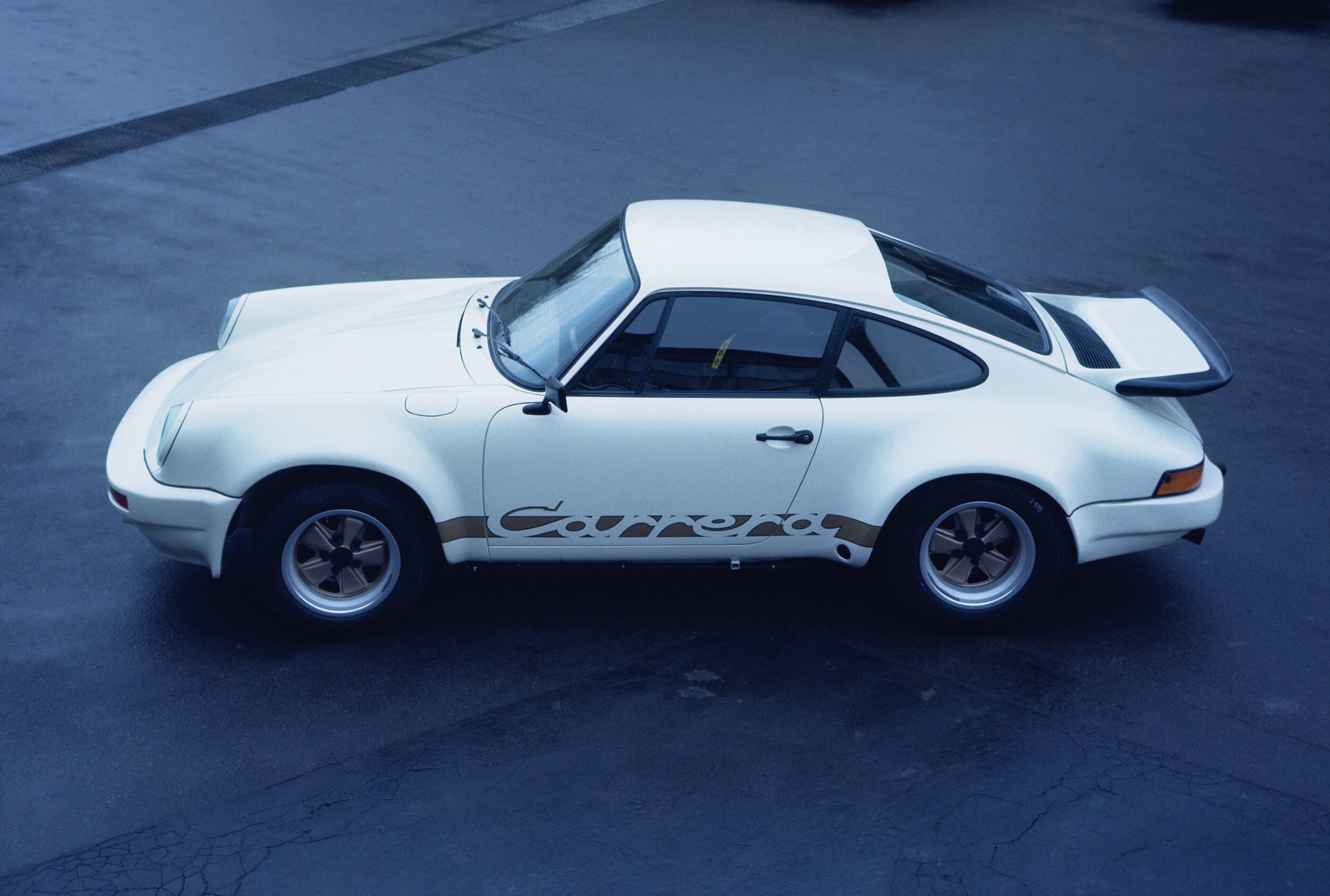

Roger Penske pondered a multitude of vehicle options for his new series. Formula Fords, Camaros, AMC Javelins and Mustangs were all considered. Penske’s closest confidant, Mark Donohue, insisted that there was no substitute for the Porsche Carrera RSR.

The IROC cars had to endure three races in baking heat, combined with punishment inflicted from superstar drivers battling for a large purse. Therefore, the machinery had to be bullet proof. Donohue eventually convinced Penske that the Porsche Carrera RSR was up to the job. Writing in his 1975 book, ‘The Unfair Advantage’, Mark Donohue believed that the Carrera RSR was: “Without a doubt the very best off the shelf production race car available at any price.” Quite the endorsement.

Donohue’s opinion carried weight. During a winter test in 1973 at Paul Ricard, the Indy 500 champion contributed to the Carrera RSR’s development. When bad weather halted testing of the 240mph 917-30 Can-Am car, Donohue hopped into the Carrera. If the weather was deemed unsuitable for any action, Donohue and Porsche engineer, Helmut Flegl, retired to the pits to exchange ideas over a bottle of Calvados. Amongst the white-knuckle rides in the 917 and sampling the local adult beverages, Donohue discovered the potential of Porsche’s latest production racer.

Before signing off on a batch of fifteen identical RSRs, Penske asked Porsche to create an ‘IROC prototype’ so he could assess the car. Essentially an RSR racer with a Targa open roof, Penske enjoyed the use of the ‘IROC prototype’ as a daily driver before Mrs Penske took ownership.

Now satisfied, Penske sent the cars directly to Riverside raceway in advance of the opening event. When the cars arrived, testing began under the supervision of Porsche engineers. On an initial fast run, Milt Minter pushed the Goodyear rubber beyond its limit and blew a tyre, forcing a swift rethink of car setup. Normally, such a task at Penske racing would be the exclusive concern of Mark Donohue. However, in the interests of calming driver cynicism around Donohue’s supposed insider advantage, Penske insisted his driver stay well clear of the project.

Penske’s Goodyear deal caused difficulties off track too. Although the IROC kingpin wanted Mario Andretti and Al Unser on the driver roster, contracts with Firestone tyres prohibited their participation.

When drivers arrived for practice in the mechanically indistinguishable Porsches, grumblings continued over Donohue’s supposed ‘Unfair Advantage’, given his status in the Penske organisation. Following his orders from Roger Penske, the quiet New Jerseyan sat patiently, holding his tongue, waiting to be called to action.

Throughout the day, the cast of IROC superstars lapped a trio of seemingly identical cars. Yet, the consensus was that one car was the runt of the litter. Keen to dispel this narrative, Donohue hopped into the unfavoured machine and went quickest. All of a sudden, the runt became the gem.

1972 F1 champion, Emerson Fittipaldi qualified on pole position for the inaugural IROC race in October 1973 at Riverside raceway. Arguably, Fittipaldi was the only driver to eclipse Donohue on pace throughout the four-race series.

However, Fittipaldi found himself sent to the back after arriving late to the pre-race briefing. F1 superstar or not, nothing less than perfection would be accepted from the troupe in Roger Penske’s circus.

Now promoted to pole position, Mark Donohue led the pack of distinctively coloured Porsches to the green flag. Donohue applied his hard-earned knowledge gained during the Carrera’s development to dominate the opening contest.

Donohue’s Can-AM arch nemesis, George Follmer, was the star of the show in race two. As one of the few drivers in the field with experience of Porsche’s unique rear engine machine, Follmer carved through the pack, claiming a convincing win. Mark Donohue wasn’t so fortunate. Excessive temperatures led to a stuck throttle, forcing Donohue out of the race.

As a consolation for his race two disappointment, Mark Donohue started the third and final race at Riverside on pole position. A win would confirm his place in the Daytona finale in February 1974. Prior to the race, another order came in from Roger Penske. Keen for a repeat of the rousing spectacle of race two, Penske urged his Can-Am champion not to pull too far ahead. Despite his loyalty to Penske, Donohue had no interest in holding back. After all, Donohue needed the cash prize with retirement looming

Dressed in an immaculate mustard yellow blazer and trademark black flat cap, Jackie Stewart quizzed the IROC superstars in pit lane for ABC Sport’s pre-race show. Speaking to the recently retired three-time F1 champion, Donohue hinted at the trepidation he faced: “I’m more nervous now than I’ve been in a long time” revealed the polesitter.

Once Donohue climbed aboard his jet-black Porsche, he was untouchable. As the other drivers struggled to adapt to the unique nuances of the RSR, Donohue cleared off at the front. After taking the checkered flag, Donohue returned to pit lane expecting the customary fanfare. Yet, none appeared. Given his understanding of the fickle Porsche, the paddock had expected Donohue to win anyway. Nevertheless, with two wins from three races, Donohue had booked his place in the Daytona finale.

After the Riverside event, the Carrera’s drivetrains were sent back to Germany to be rebuilt by Porsche. Meanwhile, each chassis would be put through the famously painstaking ‘Penske preparation’ at the team’s workshops.

Adapting the Porsches to the demands of the high banks of Daytona road course would take some work. IMSA champion, Peter Gregg, was dispatched alongside Al Holbert to complete testing duties. Curiously, on this occasion, Donohue’s feedback was asked for. Suggesting a slightly softer set up than Porsche’s recommendation, some may have argued that Donohue was exacting an ‘Unfair Advantage’ by influencing car set up. Bobby Unser believed that Donohue was the only driver in the IROC field who didn’t despise driving the unique Porsches.

‘Unfair Advantage’ or not, Donohue arrived at Daytona for his farewell race. After sealing the 1973 Can-Am title at Riverside in the all-conquering Porsche 917-30, the Penske ace had announced his planned retirement from the sport. With civvy street lurking, Donohue wanted to hang up his helmet on a high.

Fittingly, Donohue’s last race involved a titanic tussle with George Follmer. In a battle of wits, Donohue deployed every trick from the back pages of his playbook to vanquish Follmer and win the IROC championship. On the cooling down lap, corner workers gathered to salute the all-American hero and wish him well for life out of the cockpit.

Many grumbled that Donohue enjoyed a crucial insider’s edge, even in a series where parity of equipment was paramount. However, Donohue’s ‘Unfair Advantage’ was actually no secret. No driver before him, and very few since, have displayed the sheer work ethic of Mark Donohue. This was the real key to winning the inaugural International Race of Champions.

Penske’s Porsche Carrera RSRs enjoyed one solitary season of IROC competition before being sold off to a variety of owners. Many of the cars raced on for over a decade. Nowadays, when an IROC Porsche passes across the auction block, these historic 911s command over two million dollars.

PHOTO CREDIT TEAM PENSKE AND HONDA